(Co-authored with Mita Choiudhury)

In a public health emergency, the role of the government is expected to be dominant as private provisioning is likely to be sub-optimal. Yet, in a health system, which is largely dominated by the private sector, a public-private interplay is inevitable. In this article, we explore the testing and treatment space for Covid-19 in India and compare and contrast the roles of public and private health sectors. In the absence of any comprehensive database on the issue, we scanned through the daily Covid bulletins, dashboards and websites of the four states (Delhi, Maharashtra, West Bengal and Tamil Nadu) to examine the relative availability of beds and their occupancy rates in the two sectors. Information on testing laboratories in the public and private sectors across states were also culled out from the website of the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR). In addition, in the four selected states, the spread of laboratories for testing in the four metros vis-à-vis others within the state was examined. The distribution reported here pertains to the months of June, July and August 2020.

Sharing of Covid Testing Load between the Public and Private Sectors

The government is expected to play a larger role than the private sector in testing, as this has positive externalities and can reduce the spread of the disease. Social benefits outweigh the private benefits, and this renders the role of the private sector sub-optimal.

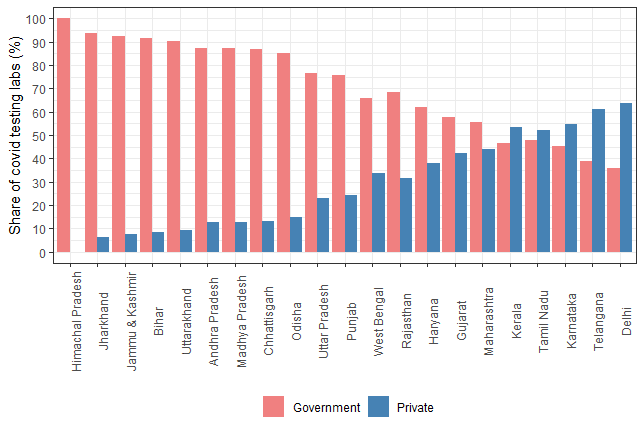

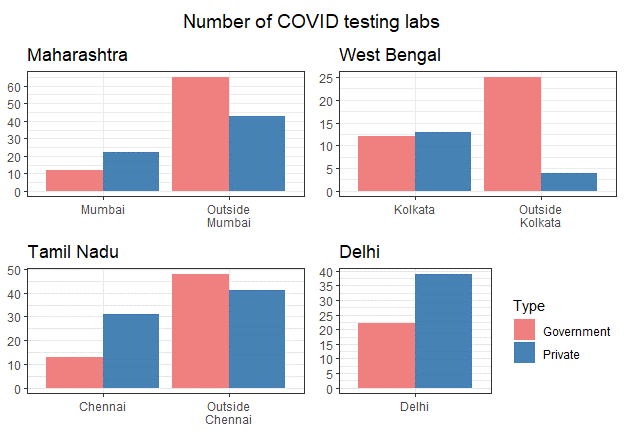

Data suggests that Covid testing in India is indeed dominated by the public sector. Of the laboratories operating across 21 major Indian states, nearly two thirds are in the public sector. The dependence on government laboratories is particularly high in the relatively poor and hilly states of the country (Fig 1). The private laboratories are largely confined to the richer states. This is mirrored in the fact that three of the four states with metro cities (Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Delhi), have more private than government laboratories. The ratio of government to private laboratories was even more skewed in the four metros. In Delhi, there were 39 private laboratories as opposed to 22 government laboratories. In Chennai and Mumbai there were 31 against 13, 22 against 12 respectively. In Kolkata, the number of laboratories in public and private were nearly equal (Figure 2). Outside the metro cities however, the ratios are reversed. There are more government laboratories than private ones, which point towards the fact that while the private sector is confined to richer regions due higher ability to pay by individuals, the government plays a larger role in equitable access and distribution.

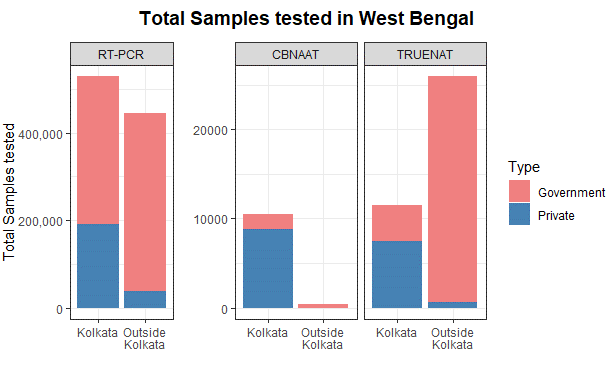

The ratio of laboratories in public and private sectors need not correspond to the actual distribution of tests in the two sectors. Information on actual number of Covid tests in government and private laboratories are available only for West Bengal. Figures reveal that most of the tests in the state were conducted by government laboratories (Figure 3). Outside Kolkata, testing was even more heavily dominated by government laboratories, and the role of the private sector was negligible.

Figure 1: Share of public and private Covid testing laboratories in States (per cent)

Figure 2: Spread of COVID testing labs in metro and non-metro areas in four major states

Figure 3: Break-up of samples tested in metro and non-metro areas in West Bengal

Sharing of Covid Treatment Load between the Public and Private Sectors

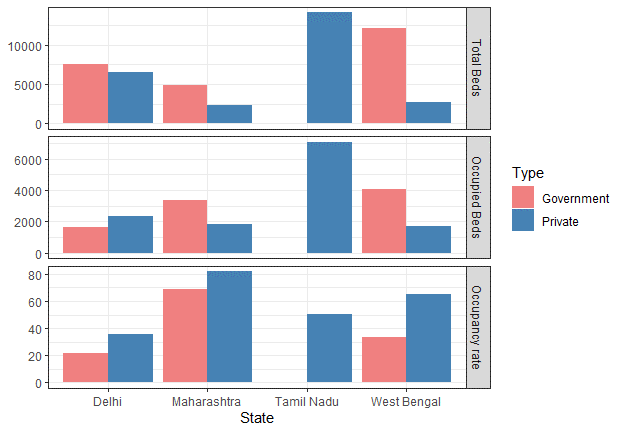

In treatment, the role of the private sector has been larger than in prevention. In Delhi, Maharashtra and West Bengal, the government designated more beds than the private sector, but the pattern of actual usage was different (Figure 4). In Delhi, the occupancy rate was much higher in private facilities than public (35 vs. 21 per cent), which resulted in higher usage of beds in the private sector. Even in West Bengal and Maharashtra, the occupancy rate in private was more than the occupancy rate in public facilities (65 vs. 33 in West Bengal and 81 vs. 68 in Maharashtra). The high occupancy rates in private hospitals point towards the fact that despite availability of public beds, people choose to use beds in private facilities.

Figure 4: Private and public hospital beds for Covid Treatment

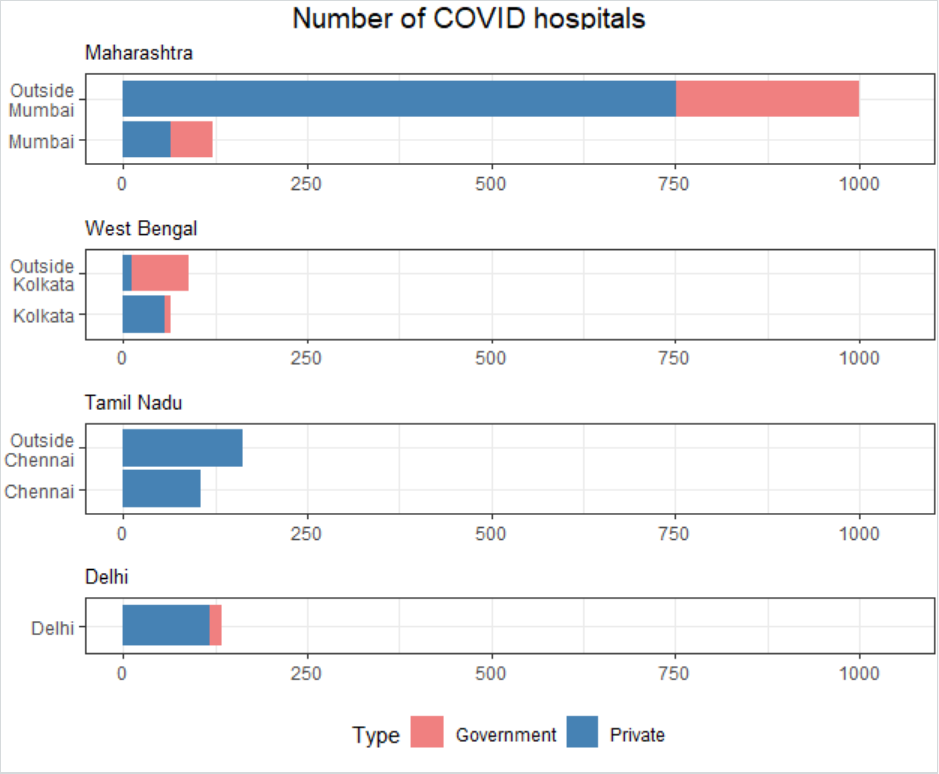

Interestingly, metro cities like Kolkata and Delhi had more private facilities than government ones (Figure 5). As in the case of testing laboratories, this is likely due to higher ability to pay by individuals in these relatively rich cities. Outside metros there was a contrast between Maharashtra and West Bengal. While, outside Kolkata, government hospitals and government requisitioned hospitals outnumbered private Covid hospitals, in Mumbai it was vice-versa (Figure 5). In general, West Bengal had a higher dominance of the public sector than Delhi or Mumbai. In fact, the West Bengal government requisitioned several private hospitals for Covid treatment. This is unlike Delhi, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu, which have not requisitioned, but reserved a specified percentage of beds in private hospitals for Covid care and capped prices in them.

Figure 5: Covid hospitals in metro cities and outside metro cities.

The regulation of prices in private hospitals by the government of Maharashtra, Delhi and Tamil Nadu was expected to ease the financial burden on households. However, the capped prices for patients with co-morbidities had to be left relatively open and this has made the price regulation less effective. In patients with co-morbidities, the volume of drugs and investigations required for treatment was uncertain and could not be prespecified. In most cases, the packages defined under capped rates included basic services like bed charges and ventilator charges and excluded high-end treatment. Even in the basic package, there were variations. Delhi included the cost of PPE in the basic package, while Maharashtra did not. These features have induced various loopholes in the implementation of price regulations.

In sum, in the limited period of this analysis, the government seems to have played a dominant role in prevention in the form of testing, whereas the role of the private sector has been more prominent in treatment and in larger cities.

Dweepobotee Brahma is Fellow, NIPFP, New Delhi.

The views expressed in the post are those of the authors only. No responsibility for them should be attributed to NIPFP.