Indian history has been well documented by great writers like Dadabhai Naoroji, Romesh Chander Dutt, Jawaharlal Nehru and others. Shashi Tharoor has turned the same material into a gripping page turner. With his characteristic wit, biting sarcasm and gifted writing, he has produced a bestseller that will re-ignite thinking and debate and open the eyes of the younger generation in India and hopefully in Britain on this “era of darkness”.

Tharoor has authoritatively debunked the work of colonial apologists like Niall Ferguson and Nirad C. Chaudhuri, and meticulously documented the systematic loot and plunder of India. The section on famine relief is probably the most damaging example of heartless colonial policy, allowing 35 million to die — more than the numbers that were killed by Stalin’s collectivisation and Mao’s Cultural Revolution — while food was being exported out of the country to help the British war effort. The great Winston Churchill emerges from the quotes in the book as horribly racist and perhaps even criminally negligent.

Tharoor documents how British colonialism was a commercial project to extract revenue and serve as a market for British goods. How India was systematically de-industrialised using examples of textiles, steel and ship-building; and how various land settlement systems were gradually modified to extract more and more revenue and reduced the peasantry into penury. But Tharoor’s argument that, as a result, landlessness was first witnessed during British rule is not backed by evidence. The famous economic historian Dharma Kumar showed that landlessness existed before the British arrived. But it probably increased hugely during British rule.

Tharoor’s new contribution is that he even takes apart the commonly accepted argument — such as that made by former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh — that the British Empire left quite a bit of good in India, from democracy, rule of law, free press to the railways, civil service and the army. Tharoor systematically tries to debunk these arguments and grudgingly admits to only three benefits of British rule — the English language, cricket, and tea but even these, in a hilarious chapter, he regards as unintended benefits. Any of these benefits could have been brought to India without, as he says, “the exploitation, distortions and deracination that accompanied its acquisition by the colonized.” Tharoor, a sitting MP, would even prefer a Presidential system over Westminster-style parliamentary democracy.

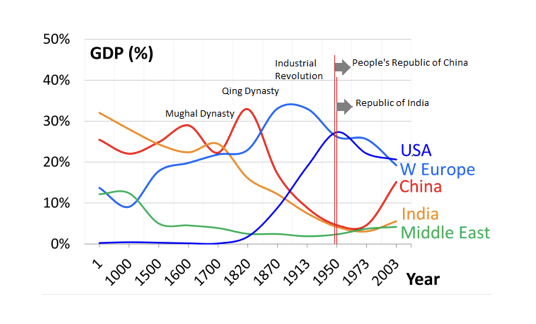

Where Tharoor’s argument is weak is in his major point that British rule helped reduce India’s share of global GDP from 23 per cent when they entered India to only 4 per cent by the time they left. But as Angus Maddison’s figures show, India’s GDP share was declining before the British came to India — except for a brief period of about 100 years during the Mughal period — and continued to decline some 30 years after they left India, when the economy grew much faster than during British rule but yet at 3.5 per cent per year, dubbed the Hindu growth rate by Prof Raj Krishna — slower than the rest of the world. All one can say is that British colonial rule, often portrayed as able administration, did not arrest the decline and probably perpetuated it for another 200-odd years.