Indian Economy in Turbulent Times: FY 2025-26: Mid-Year Macroeconomic Review

Rudrani Bhattacharya, Associate Professor, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, New Delhi, India}. email: rudrani.bhattacharya@nipfp.org.in

Manish Gupta, Associate Professor, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, New Delhi, India}. email: manish.gupta@nipfp.org.in

Vrinda Gupta, Assistant Professor, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, New Delhi, India}. email: vrinda.gupta@nipfp.org.in

Madhur Mehta, Research Fellow, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, New Delhi, India,}. email: madhur.mehta@nipfp.org.in

Sudipto Mundle, Chairman, Centre for Development Studies}. email:

|

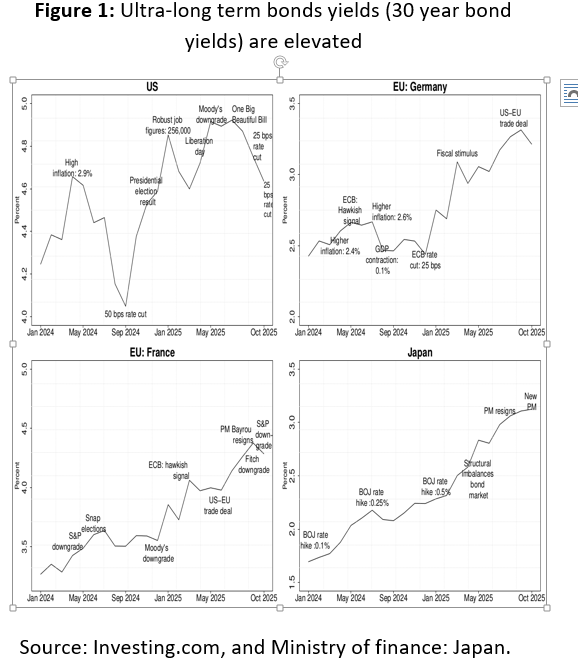

Recent global developments Rising fiscal concerns in advanced economies have hardened the long-dated bond yields, but stock markets continue to downplay fiscal concerns: Despite central banks across the advanced economies easing monetary policy, the ultra-long term bond yields have risen (Figure 1). Japan is an exception to this as rising food prices, and labour costs have induced the Bank of Japan to increase interest rates. Here, ultra-long term bond yields imply yields on bonds with 30 year maturity.

India’s external sector in the context of recent global developments

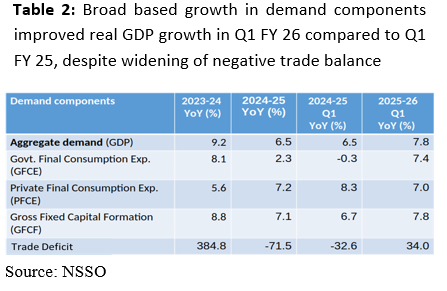

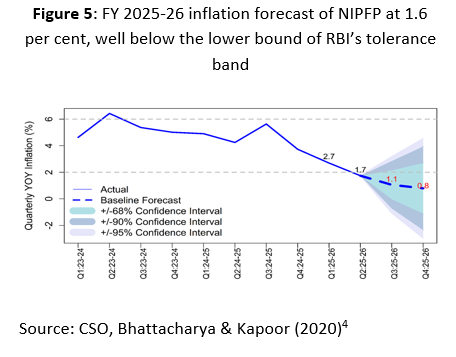

(1) In the preceding two years, the high 9.2 per cent real GDP growth of FY 24, driven by the multiplier effect of high public sector capex, had moderated to 6.5 per cent in FY 25 mainly due to the sharply reduced growth of public consumption expenditure. Investment growth also decelerated in FY 25 (Table 2). This was despite the rise in private consumption demand growth and narrowing of the real trade deficit in FY 25. (2) The factors which were driving up rural demand since 2023-24, such as good monsoon and the surge in pulse prices, have been moderating. However with favourable monsoon effects during kharif time this year, rural demand may also revive in H2 FY 26. (3) Rudrani Bhattacharya, Bornali Bhandari and Sudipto Mundle (2023), “Nowcasting India’s Quarterly GDP Growth: A Factor-Augmented Time-Varying Coefficient Regression Model (FA_TVCRM),” Journal of Quantitative Economics, Volume 21. (4) Rudrani Bhattacharya and Mrikankshi Kapoor, (2020) “Forecasting Consumer Price Inflation in India: Vector Error Correction Mechanism vs. Dynamic Factor Model Approach for Non-Stationary Time Series.” NIPFP Working Paper No. 323. PB_2025_48 |

Monetary policy and Financial sector developments

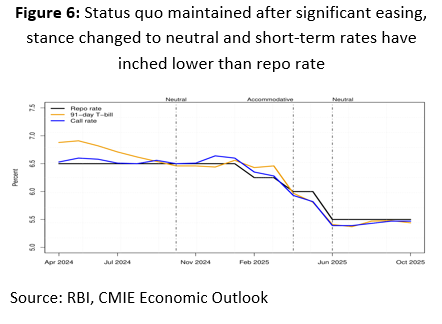

As a result of these actions, the short-term rates, represented by the 91-day treasury bill (t-bill) rates, have inched lower than the repo rate. Furthermore, liquidity infusion in the form of Daily Variable Repo Rate Auctions (VRR), Open Market Operation (OMO) purchases of government securities and USD/INR buy/sell swaps by the RBI from January 2025 end till June 2025 resulted in surplus liquidity in the banking system. The uptick in government spending has also contributed towards this. As a consequence, the weighted average call money rate has also inched lower than the repo rate.

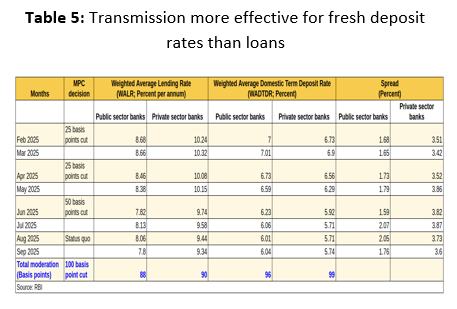

Though bank margins can come under pressure during an easing cycle, in the current cycle the spread between the fresh deposit and lending rates indicate that bank margins are not only healthy but even excessive. This is especially so in the case of private sector banks.

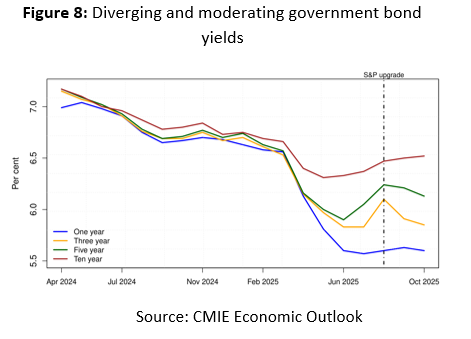

Subsequently, bond yields had started hardening for multiple reasons: the change in monetary policy stance back to neutral, expected revenue loss due to rationalisation of the Goods and Services tax (GST) and concerns about the 50 percent tariff imposition on India by the US. More recently, during September and October, bond yield movements have diverged. Long-term yields like the 10-year bond yield have hardened in response to the higher supply of long dated securities as indicated by the borrowing calendar for the second half of the current financial year. On the other hand, the short-term yields (i.e., 1-, 3-, and 5-year bond yield) have moderated tracking lower inflation. This steepening of the yield curve indicates a shift in investor preferences in favour of short maturity bonds and also a shift in preference from government bonds to corporate bonds and equity as discussed further below.

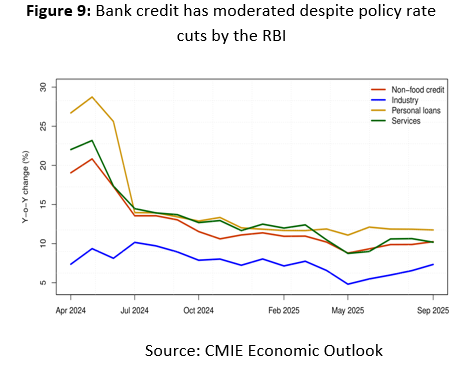

Bank credit moderation comes as a result of corporates increasingly tapping the capital markets for funds: Faster transmission of monetary policy rate cuts towards bond yields implied that issuances of corporate bond yields became cheaper (Figure 10). As a result, corporates (or large industries) have increasingly issued corporate bonds to raise funds instead of borrowing from banks. Thus, during the June 2025 quarter, where monetary policy was eased by a cumulative 75 basis points (25 basis points in April 2025 and 50 basis points in June 2025), corporates raised around Rs. 3.29 trillion crores through corporate bonds. However, all these corporate bonds are being issued through private placement route. Through this route companies sell bonds directly to a select group of investors rather than to the public. Such investors tend to hold the bonds till maturity, thereby making the secondary market illiquid.

Apart from corporate bonds, fresh equity issuances by corporates have also risen. Most of the action around fresh equity issuances is concentrated in Initial Public Offering (IPO). Small and medium enterprises along with large corporates are increasingly raising funds through the equity market. During both the June and September 2025 quarters, funds raised through equity markets surged past the levels raised during the same quarters the previous year. In the September quarter, in particular, a total of Rs. 210 billion was raised through IPOs by 134 firms. This quarter registered the largest wave of IPO listings since December 1996. The IPOs were mostly floated by firms from the manufacturing and non-financial services sectors. However, it is important to keep an eye on whether these funds are being raised for actual physical investment or to exploit arbitrage opportunities in the financial markets.

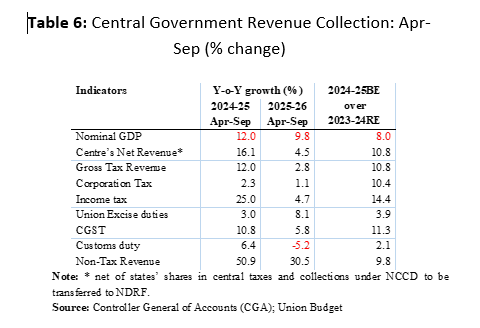

On the expenditure front we see a massive increase in the growth of capital expenditure (40 per cent) during April-September 2025 as compared to a sharp contraction of 15.4 per cent during a similar period in the previous year (Table 7). Revenue expenditure growth fell to 1.5 per cent while the total expenditure growth was 9.1 per cent as compared to a contraction of -0.4 per cent during H1-2024-25. The high total expenditure growth during H1-2025-26 is attributed to a sharp increase in capital expenditure. Major subsidies of the union government comprising food, fertilizer and fuel subsidies contracted by (-) 5.7 per cent, mainly due to the contraction in food subsidies by as much as (-)27 per cent during this period.

The government has set the Fiscal deficit-GDP (FD-GDP) target at 4.4 per cent for 2025-26, lower than the earlier FD-GDP reduction goal of 4.5 per cent by 2025-26 which was announced by the finance minister in her 2021-22 budget speech.

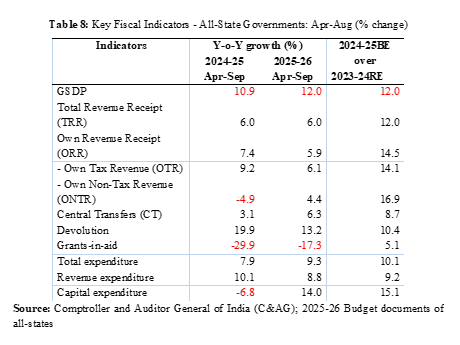

On the expenditure side, the combined capital expenditure of all states increased by 14 per cent as compared to a contraction of (-) 6.8 per cent in 2024. Revenue expenditure growth at 8.8 per cent during Apr-Aug 2025 was lower than that during the same period in 2024-25 as evident from Table 8. For 2025-26, all-state revenue expenditure is budgeted to grow by 9.2 per cent and capital expenditure by 15.1 per cent. Total expenditure which grew by 9.3 per cent during Apr-Aug 2025 is budgeted to grow by 10.1 per cent in 2025-26. |