The decision to simplify India's Goods and Services Tax (GST) into a primary two-slab system of 5% and 18% is a huge win for tax reform1. This highly anticipated shift replaces a complex, multi-tiered architecture and is expected to boost the economy by making compliance easier, globally competitive, and—most importantly—slashing costs for consumers.

Yet, a major structural headwind persists, the Inverted Duty Structure (IDS). This anomaly, which taxes raw materials higher than the final product, traps capital in the form of unutilized Input Tax Credits (ITC). For domestic manufacturers, this means paying high upfront costs and then battling a slow, refund system to get their money back. This is devastating for the financial health of MSMEs. Because they rely entirely on steady cash flow and have few credit options, having funds locked up directly cripples their ability to run production cycles, buy supplies, and settle vendor payments, leading to a vicious and unsustainable financial spiral. Unfortunately, the recent GST rate changes, while helpful, only offered partial relief, failing to solve the problem completely and, in some cases, shifting the IDS challenge into new sectors2.

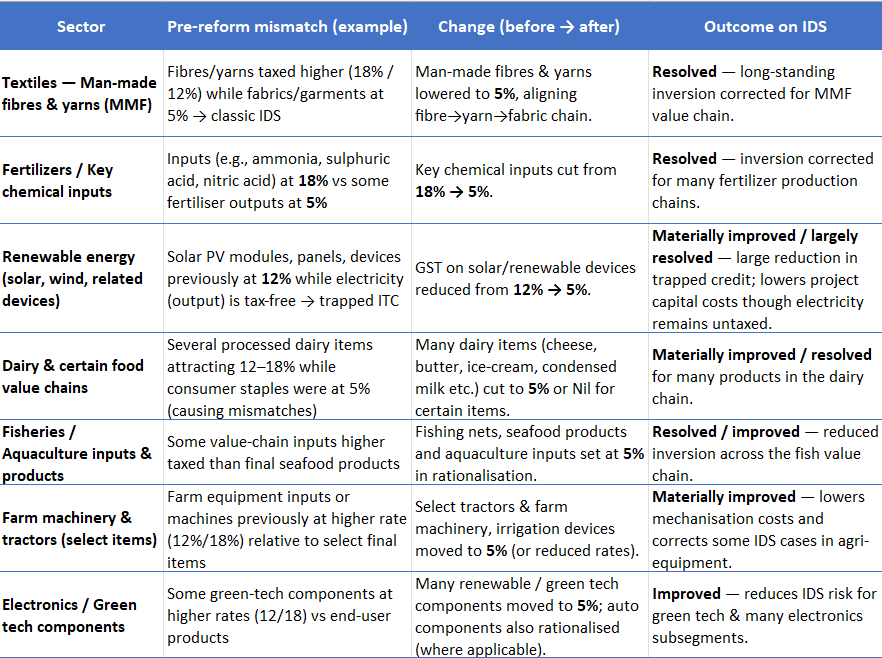

This article seeks to examine select sectors where the issue of IDS has either been resolved, worsened, or newly introduced, by analysing key inputs and comparing GST rates before and after the reform.

Where the New Policy Helped

- Textiles3: The man-made textile industry was a classic example of IDS. Inputs like man-made fibre were taxed at 18%, while finished clothes were at 5%. The new policy has largely fixed this by cutting the tax on key inputs down to 5%. Fibre-Yarn-Fabric rate has been aligned. This is expected to ease the financial strain for manufacturers, especially small businesses.

- Fertilizers & Agriculture4: The fertilizer sector had a similar problem, with chemicals taxed at 18% while the final product was at 5%. The government cut the tax on these chemical inputs (Urea, Single Super Phosphate (SSP), Diammonium Phosphate (DAP), Muriate of Potash (MOP), Complex fertilizers, Key raw materials (sulphuric acid, nitric acid, ammonia) to 5%, which is expected to save the industry billions in refunds. For 12 Bio-Pesticides and several micro-nutrients, GST was reduced from 18% to 5%. This move helps lower costs for farmers.

- Solar Energy5: The solar industry has a unique IDS problem because electricity, the final product, is tax-free. This means all the tax paid on inputs gets stuck. The new policy helps by reducing the tax on solar components from 12% to 5%. This doesn't eliminate the issue, but it significantly reduces the amount of trapped money, which can lower the cost of solar projects by 10-15% and make clean energy more affordable.

- Dairy & Food Value Chains6: The GST overhaul brought welcome relief to the dairy and food-processing sector. Items like butter, cheese, and condensed milk moved from 12% to 5%, while milk and paneer were made tax-free. By aligning the tax rates on inputs and outputs, the reform eased much of the earlier mismatch that trapped working capital for processors and cooperatives.

- Fisheries & Aquaculture7: For the fisheries sector, GST cuts on fishing nets, seafood, and aquaculture inputs—such as pumps and aerators—from 12–18% to 5% have levelled the playing field. The change reduces cost pressure, improves liquidity for small operators, and makes India’s seafood exports more competitive globally.

- Farm Machinery & Equipment8: Agricultural machinery and tractor components, once taxed at 12–18%, now attract just 5%. This rationalisation lowers the cost of farm mechanisation and fixes long-standing tax distortions that hurt rural manufacturers and suppliers.

- Electronics & Green Technology9: The reform also extended relief to green-tech and electronic components. Many renewable-energy devices and eco-machinery have been moved to the 5% bracket, helping reduce input costs and support domestic manufacturing in the clean-energy space.

Table 1: IDS Anomalies Addressed and Minimized

Source: Various Press Releases of PIB

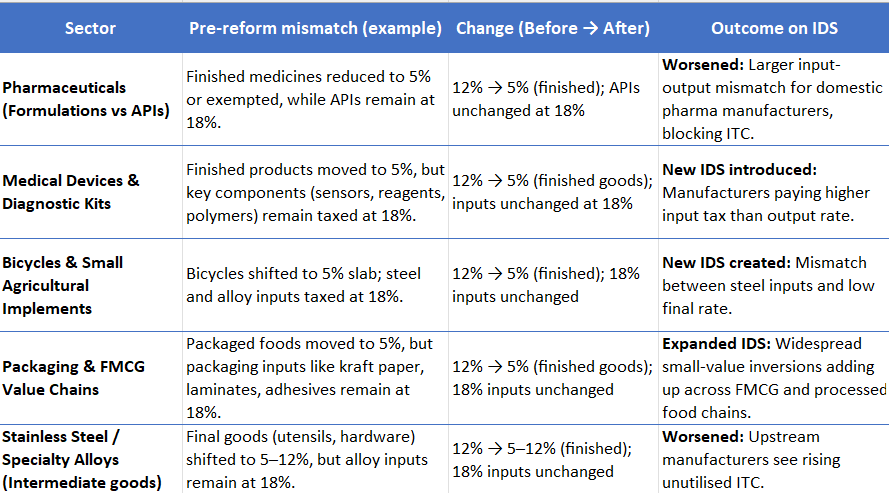

Where the Problem Got Worse

GST-2.0 fixed headline rates but the redistribution (many finished goods to 5%) without matching input cuts created fresh inversions in sectors where raw materials or intermediate inputs stayed at 12–18%. That increases the spread of unutilised ITC and intensifies refund/working-capital pressure for affected manufacturers.

- Pharmaceuticals / Medical devices10: The pharmaceutical industry was already struggling with an IDS problem. The new policy, while aimed at making medicine cheaper for consumers, has made it worse for domestic manufacturers. The tax on finished medicines was cut from 12% to 5% or even zero for life-saving drugs, but the tax on key ingredients (APIs) stayed at 18%. This has widened the tax gap, creating more working capital problems for companies.

- Bicycles / Agricultural machinery / Tractors11 : They now have a 5% tax, but the steel used to make them is still taxed at 18%. This is a new and significant tax gap.

- Consumer Goods12: Many packaged foods and consumer goods moved to 5%, but their packaging materials (kraft paper, laminates, some adhesives) stayed at higher slabs — producing widespread, small-value inversions across FMCG value chains that cumulatively may block significant working capital.

- Some export-linked / stainless-steel upstream segments13: Where final products benefited from cuts, upstream inputs like stainless steel and specialty alloys stayed at 18%, worsening inversion risks for firms in clusters that supply both domestic and export markets.

Table 2: New and Worsened IDS Anomalies

Source: Various Press Releases of PIB

The recent changes to the GST are a big step towards tax-rationalisation, but the fact that the inverted duty structure is still in place and in some cases getting bigger shows that the job is far from done. The big gap between the 5% and 18% tax brackets keeps causing problems, tying up working capital and making it harder for some important sectors to make things in the country. In the future, the goal should be to slowly bring these rates closer together to reduce differences, while also learning from the best practices of other countries.